As a companion project to our work exploring Bernard Stiegler’s understanding of value, Modeling Memory in the Anthropocene seeks to illuminate Stiegler’s theory of memory and open a critical dialogue regarding its role, or lack thereof, in the field of Memory Studies. Through the creation of semantic ego-networks from two corpora, one Stieglerian and the other rooted in the conventional study of memory, we endeavored to construct the preliminary framework for a three-tiered argument advancing elements of Stiegler’s notion of memory that we contend are excluded in the field of Memory Studies to the detriment of itself.

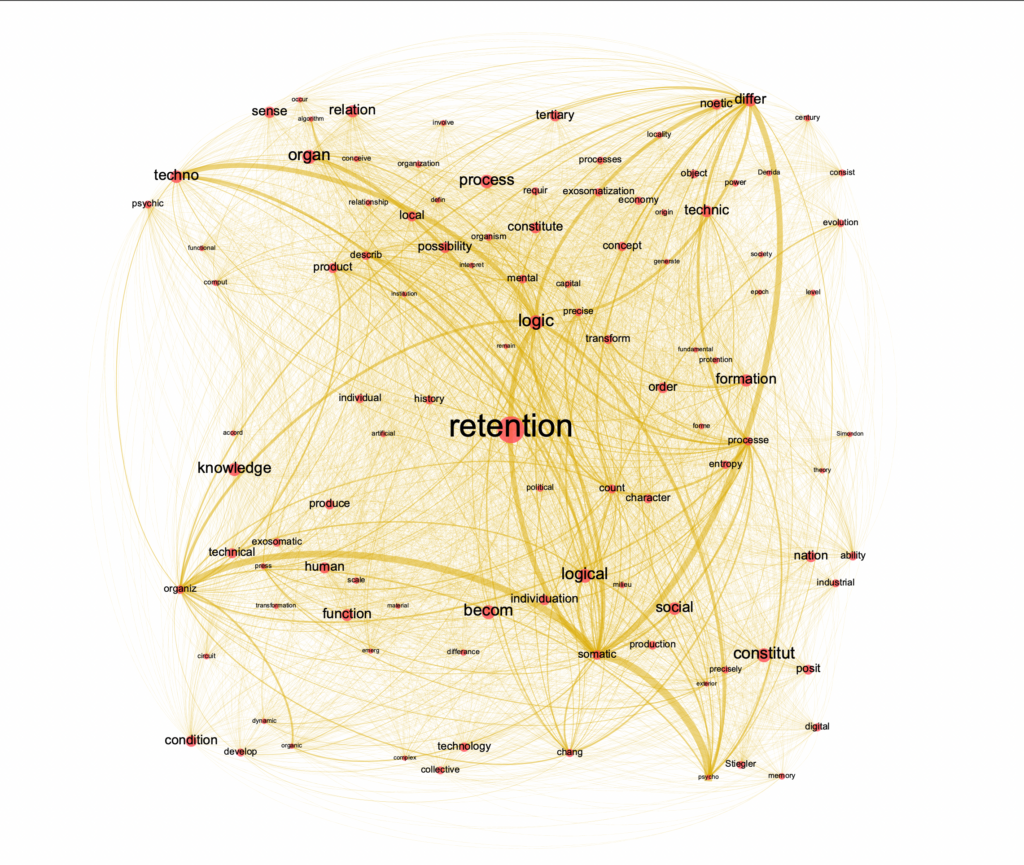

Click here to view an interactive version of the Stieglerian Retention Ego-Network.

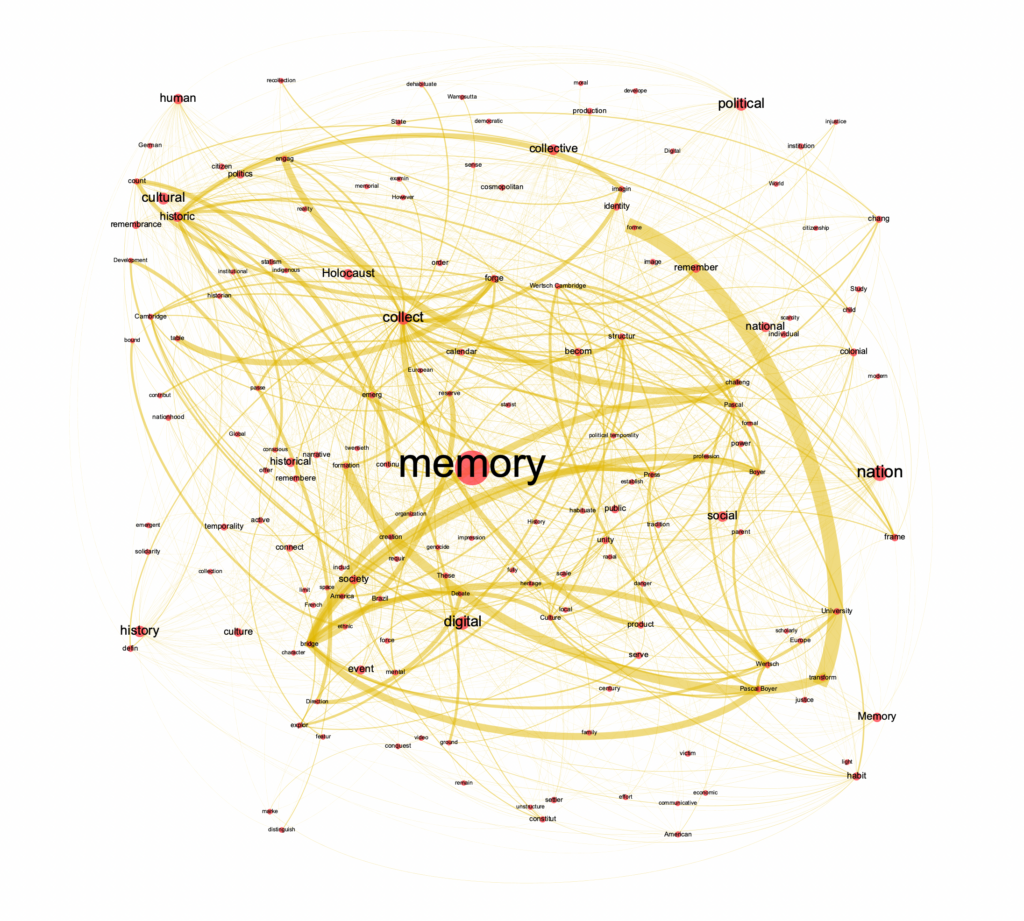

Click here to view an interactive version of the Memory Ego-Network.

In order to demonstrate Bernard Stiegler’s potential usefulness for the field of memory studies, I want to show that he was first and foremost a philosopher of memory. He is often charged with being a philosopher of technology, but this is only true to the extent that, for Stiegler, technology is itself memory, or more specifically, that technologies are systems and mobilizations of memory. It is not only true that our individual memories depend on technical supports, such as writing, for their place in our psychic experience, but also that writing and all technical artifacts are themselves memories. All technical objects (whether they be axes, paintbrushes, toys, video games, weapons, greeting cards, or books) are spatializations of a temporal flux that exist as a memory in the material world of the human. This will be made clearer in what follows.

This all needs to be placed in the context of a greater philosophy of life wherein Stiegler conceives of life itself as memory. He shows us that life is the several great epochs of memory insofar as life is that which is retained in the cosmos, is “the improbability of the past persisting into the present”, in a way that is not true for inorganic matter before the advent of life (Psychopolitical Anaphylaxis, 34). Each epoch is characterized by how memory is retained and what it can do. This begins with phylogenetic memory which is encoded and transmitted via the genome but which can not learn lessons. The second epoch is that of the epigenetic memory of animal life, which is stored in the brain, allowing the individual animal to learn lessons in the course of its life but which it is incapable of passing on to others. The genesis of the kind of beings that we are commences the epoch of epiphylogenetic memory wherein memory is stored not just in the brain but also in inorganic matter (such as stone or clay or silicon) and thus lessons can be passed on to others and to future generations. The selective criteria by which we behave is formed by this world or prior exteriorizations that make up the basis of what it is possible for us to remember as individuals.

It is on this basis that we propose that a network graph could be conceived of as a memory project. For much of memory studies, the work that is often considered are archives, oral history collections, repositories of photos or videos. From a Stieglerian perspective, these are all tertiary retentions, and it is retentions like these that form the funds for collective memory. However, from a Stieglerian perspective, memory studies miss out on the understanding that writing of all kinds is also memory. The words you are reading right now are the exteriorizations of our memories that we have left a trace of for you to read. It is from this perspective that a map or a graph can also be considered memory work. It is a particular way to organize and transmit memory. We have created two network graphs: one displaying a network of all the words that tend to co-occur with “memory” in a sample of memory studies work; and another displaying what words tend to co-occur with “retention” in the work of Bernard Stiegler and the Internation Collective. These maps can thus be viewed as visualizations of two different collective memories of two different collectives. The purpose of these two maps of collective memory is to demonstrate how memory is used differently in Stieglerian work from how it is used in memory studies, with the hope that this can provide useful insights for memory studies and open up new lines of thought as well as new practices for memory projects.

When looking at the graphs, a few things stand out. The first is the prevalence of “technics”, “tertiary”, “techno”, “technology”, and “artificial” in the Internation graph, and the absence of any of this from the memory studies graph. The second is the prominence that words like “nation”, “national”, “political”, “collective”, “cultural” have in the memory studies graph and the absence of any words like “psychic” and “mental” that are included in the Internation one. Lastly is the large connection that “knowledge” has with memory in the Internation graph and the concurrent absence of “knowledge” from the memory studies graph. From the lines of thought opened up by these insights, we can say that, from a Stieglerian point of view, there are three theoretical points concerning memory which are left unthought by the field of memory studies:

1. No attention is paid to the centrality of tertiary retention for memory-production, memory-transmission, and memory-transformation, and this results in a missed opportunity for a truly radical digital memory studies worthy of the name. Although mediation is discussed sometimes in the field, it is a concept made absolutely inessential to the thought of memory by it.

2. Individual memory, along with technical memory, is repressed by the notion of collective memory, leaving the discipline without a stable concept of “memory”.

3. A conflation of knowledge with information, leaving us without an understanding of what makes collective memory properly collective.

Points 1 & 2

Stiegler’s theory of memories amounts to a threefold conception of retention, wherein the three forms of epiphylogenetic memory that make up our experience as humans are primary retention, secondary retention, and tertiary retention.

1. Primary retention is what is often referred to as perception. It is the retaining of the “now” in the “now” of sensory perception. It is a retaining of the world we are part of, a world that is made sensible to us by the possibility of primary retention. Our stream of attention, or consciousness, is composed of a series of “now’s” of primary retention.

2. Secondary retentions are what are often referred to as memory as such. They are primary retentions that have been retained in the psyche of the individual. They are primary retentions that have become secondary, that is, past. Secondary retentions contain secondary protentions, which are anticipations of the future based on what is past. This arrangement of secondary retention and protention form the criteria for primary retention, which is thus a primary selection. Our psyches “select” what we are to perceive in the moment of primary retention based on these anticipations of the future which are based on memories of the past. Our attention or consciousness is thus this play between secondary retention, secondary protention, and primary retention.

3. Tertiary retentions are exteriorizations of streams of attention, exteriorizations of memory such as music, writing, painting, machines, computers, etc. Some tertiary retentions are intended to be used as memory supports, such as calendars and books, while some are not, such as hammers and toys. However, all artifacts are non-organic organized matter, and they are all tertiary retention as exteriorizations of mental phenomena, and thus they are all exteriorizations of memory. It is crucial for Stiegler to understand that primary and secondary retention are conditioned by tertiary retention. The criteria of primary selection are formed socially through retentions that are shared, and these require the world of tertiary retentions they are embedded in order to transmit them, starting with transitional objects and speech, and passing through cultural objects of all kinds.

It is within this framework that we must think about collective memory. If one opposes social memory to individual memory, as Maurice Halbwachs does, then one misses the complex play between these three dimensions of memory, the primordial technical support of memory, and the capacity of the individual to transform social memory through their own contribution to the universal based on their singular point of view. Social memory must be conceived as a two-way street. On the one hand, social memory is that through which individual remembrance is conditioned by the socio-technical milieu of the individual. On the other hand, social memory qua technical milieu offers support for the unmemorable, the infinite, the access to which allows the individual go beyond the schema of social memory to transform it, without which social memory would be crystallized, un-transformable, strictly frozen.

Point 3

In much of the memory studies literature, there is a conflation between information and knowledge that amounts to an erasure of the crucial difference between them. This difference is so crucial, and this erasure so dangerous, because the difference between them is not a binary oppositional difference, but rather a difference that inscribes them within the same process, the process by which information becomes knowledge, and this process is essential for the transindividuation process and is a necessary condition of possibility of culture, science, and politics. Stiegler teaches us that the problems of the contemporary global economic system are fundamentally the result of the destruction of knowledge, which always bears a relation to incalculability, at the hands of an over-dependence on information, which is always calculable. If we do not understand a distinction between the two, we cannot understand the way that the hegemonic logic of calculation, which is the epistēmē of capitalism, short-circuits knowledge-production at the service of a macroeconomic model that relies on a structural stupidity (and the reliance on mere information) for its continued survival.

This difference between information and knowledge can be better understood through Stiegler’s post-Kantian formulation of the functions of the faculty of knowing. For Kant, the functions of the faculty of knowing were intuition, understanding, and imagination. The understanding, in Stieglerian language, is the form that secondary retentions take in the mind of the psychic individual. As discussed above, this schema (by which secondary retentions are formatted in the mind of the individual) forms the criteria by which the primary retentions of the current moment are selected in intuition. These primary retentions as given to the intuition can either be integrated into the schema of the understanding or they can contradict it. The information received in primary retention can in-form, that is de-form, the understanding and re-form it through the synthetic work of reason. This process becomes impossible when the function of the understanding becomes exteriorized as computing and information technologies. Exosomatization amounts to the exteriorization of the functions of knowing throughout its history as different tools and machines (for instance, the microscope is an example of one exteriorization of the function of the intuition). Over-reliance on any given tool or technology has the potential to short-circuit the noetic function for which it is a supplement. And, so, as Stiegler writes, “In the current stage of the exosomatization of the noetic faculties…digital tertiary retention consists of information, that is, data, which can present itself only as formatted in terms of its a priori calculability” whereas “in the epoch of Kant, data was that which was ’given to the intuition, and which is manifold, diverse, that is, characterized by the fact that it is precisely not yet ‘formatted’” and thus has the possibility of interrupting the formatting and transforming thought by producing new knowledge (Nanjing Lectures, 82).

Under the regime of capitalism, the intuition, the understanding, and the imagination are all functionally and algorithmically integrated in such a way that only calculable data is valued and our understandings are formalized and automated and the production of new knowledge becomes impossible. Information only becomes knowledge when reason (by way of thinking with prior knowledge already constituted) transforms it into a new schema of the understanding and exteriorizes it, making it transmissible, that is, social. This new knowledge, then, becomes a collective retention and protention that becomes part of the criteria by which a social body

References:

Retention Ego-Network

- The Internation Collective. (2021). Bifurcate: There Is No Alternative. Open Humanities Press.

- Ross, D. (2020). Psychopolitical Anaphylaxis: Steps Towards a Metacosmics. Open Humanities Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2019). Nanjing Lectures: 2016-2019. Open Humanities Press.

- Stiegler, B., & Ross, D. (2018). The Neganthropocene. Open Humanities Press.

- Stiegler, B., & Ross, D. (2021). Technics & Time, 4: Faculties and Functions of Noesis in the Post-Truth Age.

Memory Ego-Network

- Blight, D. (2009). The memory boom: Why and why now? In P. Boyer & J. Wertsch (Eds.), Memory in Mind and Culture (pp. 238-251). Cambridge University Press.

- Sierp A. (2021). Memory Studies – Development, Debates and Directions. In M. Berek et al (Eds), Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Gedächtnisforschung (pp. 2-10). Springer VS, Wiesbaden.

- Kansteiner, W. (2018). The holocaust in the 21st century. Digital anxiety, transnational cosmopolitanism, and never again genocide without memory. In A. Hoskins (Ed.), Digital memory studies: Media pasts in transition (pp. 110-140). Routledge. (L)

- Garde-Hansen, J. & Schwartz, G. (2018). Iconomy of memory. On remembering as digital, civic and corporate currency. In A. Hoskins (Ed.), Digital memory studies: Media pasts in transition (pp. 217-233). Routledge. (L)

- Assmann, A. (2012). To remember or to forget: Which way out of a shared history of violence? In A. Assmann & L. Shortt, Memory and political change (pp. 53-71). Palgrave Macmillan. (L)

- Misztal, B. (2010). Collective memory in a global age: Learning how and what to remember. Current Sociology, 58(1). 24-44.

- Bruyneel, K. (2013). The trouble with amnesia: Collective memory and colonial injustice in the United States. In G. Berk, D. C. Galvan, & V. Hattam (Eds.), Political creativity : Reconfiguring institutional order and change (pp. 236-257). U. Pensylvannia P. (L)

- Hoskins, A. (2014). The right to be forgotten in post-scarcity culture. In A. Ghezzi et al., The ethics of memory in a digital age: Interrogating the right to be forgotten (pp. 50-64). Palgrave Macmillan. (L)

Halbwachs, M. (1980). Historical memory and collective memory. In The collective memory (pp. 50-87). Harper Colophon. (Original text published in 1950). (L) - Confino, A. (2011). History and memory. In A. Schneider and D. Woolf (Eds.), The Oxford history of historical writing: Vol. 5. Historical writing since 1945 (pp. 36-51). Oxford UP. (L)

- Risam, R. (2019). Introduction. The postcolonial digital cultural record. New digital worlds. Postcolonial digital humanities in theory, praxis, and pedagogy. Northwestern UP (pp. 1-23). (L)

- Nieves, A. D. (2021). Digital Queer witnessing testimony, contested virtual heritage, and the apartheid archive in Soweto, Johannesburg. In R. Risam & K. Bakers Joseph The Digital Black Atlantic. (Whole book available on Debates).

Additional Resources

- Levallois, C., Clithero, J. A., Wouters, P., Smidts, A., & Huettel, S. A. (2012). Translating upwards: linking the neural and social sciences via neuroeconomics. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(11), 789-797.